| |

Gat:lapati or

Gat:leSa, also known

as Vinayaka, is

perhaps, the most

popular of the Hindu

deities worshipped

by all sections of

the Hindus. No

undertaking, whether

sacred or secular,

can get started

without first

honouring and

worshipping him.

This is

understandable and

highly desirable,

since he is said to

be the lord of

obstacles (VighneSvara

or Vighnaraja).

However, what is not

under¬standable and

certainly not very

agreeable is his

repulsive origin and

grotesque form! Even

fo~ those who admire

Lord Siva's skill in

the surgical art of

head-transplantation,

it becomes rather

difficult to admire

the end product!

Once we successfully

manage to delve into

the mysteries of

this symbolism our

repugnance will give

rise to ,respect and

respect to reverence

and worship.

Notwithstanding the

fact that the

Gat:lapati referred

to in the famous

Rgvedic mantras, 'gat:lanam

gat:lapatim havamahe...'

(2.23.1) and 'vi~u

sIda gat:lapate...'

(10.112. 9) and the

Gat:lapati we

worship today are

strangers to each

other, all unbiased

scholars agree that

the seeds of the

Gat:lapati concept

are already there in

the 1j.gveda itself.

In the subsequent

centuries, this

concept has passed

through the mills of

the epics and the

Purat:las to produce

the Gat:lapati as we

know him today. In

any community, the

development of the

concept of God and

the modes of His

worship are as much

the products of

geographical,

histori¬cal and

cultural factors as

of mystic experience

and spiritual

realizations of the

highly evolved

persons. It is quite

reasonable to

suppose that the 'Gat:lapati-Brahmat:la-spati'

of the Rgveda

gradually got

metamorphosed into

the deity, 'Gajavadana-Gat:lesa-

Vighnesvara.'

The Rgvedic deity 'Gat:lapati-Brahmat:laspati'-also

called as Brhaspati

and Vacaspati-manifests

himself through a

vast m~ss of light.

He is golden-red in

colour.

The battle axe is an

important weapon of

his. Without his

grace no religious

rite can succeed. He

is always in '

the company of a

group (gaI)a=a

group) of siq,gers

and dancers. He

vanquishes the

enemies of gods,

protects the devoted

votaries and shows

them the right

way of life. .

Another class of ~gvedic

deities, known as

the Maruts or

Marud-gaI)a,

described as the

children of Rildra,

also have similar

characteristics. In

addition, they can

be malevolent

towards those who

antagonise them and

can cause

destruction like the

wild elephants. They

can put obstacles in

the path of men if

displeased and

remove them when

pleased. They are

independent, not

subject to any one's

sovereignty (Arajana=Vinayaka).

A perusal of these

two descriptions

will perforce lead

us to the obvious

conclusion that

GaI)apati is the

metamor¬phosed form

of the

Brhaspati-MarudgaI)a

deities. There is

nothing strange in

this, especially if

we can recognize the

transformations that

have taken place

among the various

Vedic deities, as

they were gradually

absorbed among the

gods of the later

Hindu pantheon. The

once all-important

and all-powerful

Indra was demoted to

the rank of a minor

deity ruling over

one of the quarters.

His lieutenant

Vi~I)u was elevated

to the central place

in the Trinity.

Rudra, the terrible,

became Siva the

auspicious. Many

other deities like

Dyaus, Aryaman and

Pu~an were quietly

despatched into

oblivion!

Despite the fact

that GaI)apati is a

highly venerated

and all-important

deity, his 'head'

has often been a

mystery

, for others. No

doubt, our PuraI)as

have easily 'solved'

this

problem, each in its

own way. But this

has satisfied

neither the layman

nor the scholar.

It will be extremely

interesting to bring

together, though in

brief, all the

stories about the

origin of this

wondrous deity:

(1) At the request

of the gods who

wanted a deity

capable

of removing all

obstacles from their

path of action and

fulfilment, Siva

himself was born of

the womb of ParvatI

as Gajanana.

(2) Once ParvatI,

just for fun,

prepared an image of

a child with an

elephant's head, out

of the unguents

smeared over her

body and threw it

into the river Ganga.

It came to life.

Both Ganga, the

guardian deity of

the river and

ParvatI, addressed

the boy as their

child. Hence he is

known as Dvaimatura,

'one who has two

mothers'.

(3) ParvatI prepared

the image of a chilp

out of the scurf

from her body,

endowed him with

life and ordered him

to stand guard

before her house.

When Siva wanted to

enter the house he

was rudely prevented

by this new

gatekeeper. Siva

became 'Rudra' and

got him beheaded.

Seeing that ParvatI

was inconsolable

owing to this

tragedy that befell

her' son' and not

finding the head of

the body

anywhere-meanwhile

one of the goblins

of Siva had

gourmandized it!-he

got an elephant's

head, grafted it on

to the body of the

boy and gave him

life. To make amends

for his 'mistake',

Siva appointed this

new-found son as the

head of all his

retinues, who thus

became 'GaI}apati'.

(4) He sprang from

Siva's countenance

which represents

the principle of

ether (Akasatattva).

His captivating

splendour made

ParvatI react

angrily and curse

him, resulting in

his uncouth form!

(5) GaI}eSa was

originally Kr~I:la

himself in the human

form. When Sani, the

malevolent planet

spirit gazed at him,

his head got

separated and flew

to Goloka, the world

of Kr~I:la. The head

of an elephant was

subse¬quently

grafted on the body

of the child.

Equally interesting

are the other myths

about his

adventures: He lost

one of his tusks in

a fight with

Parasu¬rama, which

he successfully used

as a stylus to write

the epic

Mahabhzirata

dictated by the sage

~yasa. He tactfully

won the race against

his brother Skanda

by circumambu¬

lating his parents

and declaring that

it was equivalent to

going round the

worlds. He thus won

the hands of two

damsels ~ddhi and

Siddhi. He cursed

the moon to wax and

wane, since the

latter derisively

laughed at him when

he was trying to

refill his burst

belly with the

sweets that had

spilled out. He

vanquished the demon

Vighnasura and

successfully brought

him under his

subjugation.

There is no

gainsaying the

possibilities of man

deve¬

loping the concept

of God and faith in

Him as a result of

his experiences

through the various

vicissitudes of life

which prove his

helplessness. He

often disposes, what

he proposes. Such a

God must needs be

allpowerful. If he

is

pleased, all the

obstacles in our

path will be

removed. If

displeased He may

thwart our efforts

and make them.

infructuous. Hence

the paramount need

to appease Him and

please Him.

What could be the

form of this

almighty God? For a

simple aboriginal

living in a group (=GaI:la)

near a forest or

a mountain, the

mighty elephant

might have provided

the clue. This might

have led to the

worship of an

elephant-like God.

He being the Pati

(=Lord) of the Gal)a

(clan or group)

might have obtained

the name Gal)apati.

As the group became

more refined and

cultured, this

Elephant God might

have been

transformed into the

present form.

However plausible or

attractive this

hypothesis may be,

it is at best a

guesswork, if not an

invention! Since

Gal)apati had gained

de facto recognition

in the hearts of

millions of

votaries, over

several centuries,

the Pural)as rightly

struggled to make it

de jure! True, they

have given very

confusing accounts.

Nevertheless they

have succeeded

in fusing together

the votaries by

giving them a

scriptural or

authoritative base.

There is certainly

no contradiction or

confusion in the

accounts as far as

the worship and its

result are

concerned.

It is a favourite

pastime of some

western scholars and

their Indian

counterparts to

'discover' a

DraviQian base for

many interesting

developments in our

cultural and

religious life and

then to 'unearth'

the further fact of

the white¬skinned

Aryan 'conquerors'

graciously and

condescend¬ingly

absorbing these,

tactfully elevating

the same to

'higher' levels all

the while. This has

naturally led to a

vigorous reaction

and these

'reactionaries' go

the whole hog to

'prove' it the other

way round! When our

Gal)apati is caught

in the web of such

controversies one

may be driven to the

ridiculous

conclusion that he

is not an Aryan

deity at all, but,

most probably,

imported from

Mongolia! It is

therefore better to

play safe, rescue

our deity from

embarrassing

situations and get

the best out of him

for our spiritual

life.

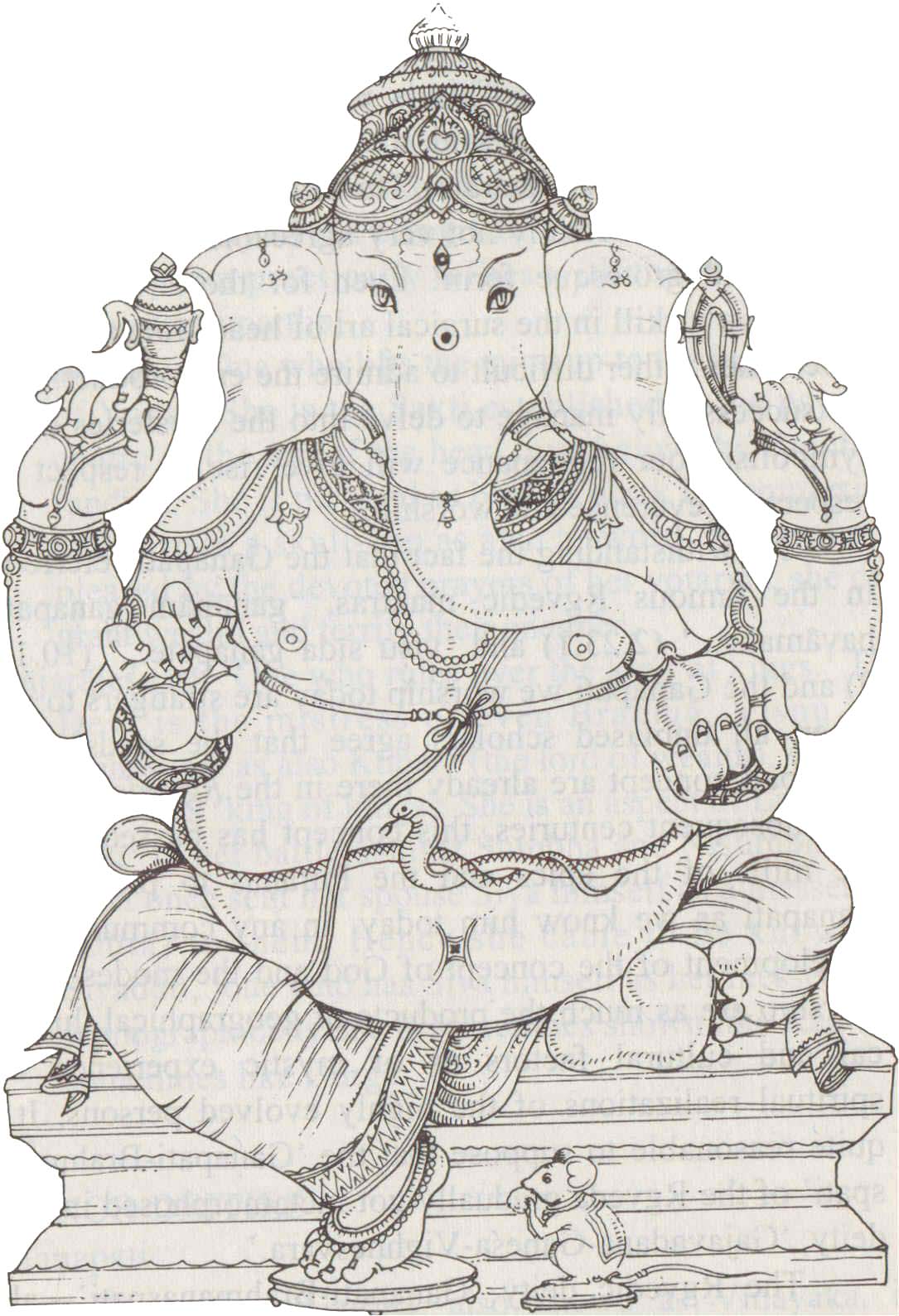

The most commonly

accepted form of

Gal)apati depicts

him as red in colour

and in a human body

with an elephant's

head. Out of the two

tusks, one is

broken. He has four

arms. Two of the

arms hold the PilSa

(noose) and Ailkusa

(goad). The other

two are held in the

Abhaya and Varada

Mudras. The belly is

of generous

proportions and is

decorated with a

snake-belt. There is

also a Yajfiopavita

(sacred Brahminical

thread), either of

thread or of

serpent. He may be

seated in Padmasana

(lotus-posture).

When the belly does

not permit this, the

right leg may be

shown bent and

resting on the seat.

Apart from beautiful

robes and ornaments,

he wears a

lovely carved crown.

The trunk may be

turned to the left

or to the right.

He is normally seen

helping himself to

liberal quan¬

tities of Modaka (a

kind of sweet).

A mouse, of

ridiculously small

proportions, is seen

near him, nibbling

at his share of the

sweets, hoping

perhaps, to gain

enough strength to

carry his master!

A third eye may

sometimes be added

on the forehead,

in the centre of the

eyebrows. The number

of heads may

be raised to five.

The arms may vary

from two to ten.

Lotus, pomegranate,

water-vessel,

battle-axe, lute,

broken tusk,

sugarcane, ears of

paddy, bow and

arrow, thunderbolt,

rosary, book-these

are some of the

other objects shown

in the hands. His

Sakti is often shown

with him as sitting

on his lap.

Sometimes two Saktis,

B.ddhi* and Siddhi,

are also shown.

Let us now make an

attempt at

unravelling this

symbology.

'GaJ).a' means

category. Everything

that we perceive

through our senses

or grasp through our

mind can be

expressed in terms

of kind, of

category. The

principle from which

all such categories

have manifested

themselves is

GaI).apati, the Lord

of categories. In

effect, it means the

origin of the whole

creation, God

Himself.

A common Sanskrit

word to denote the

elephant is 'Gaja'.

Hence the name

Gajanana or

Gajamukha

('elephant-faced')

for GaI).apati. But

the word 'Gaja' has

a much deeper

connotation. 'Ga'

indicates 'Gati,'

the final goal

towards which the

entire creation is

moving, whether

knowingly or

unknowingly. 'Ja'

stands for 'Janma,'

birth or origin.

Hence 'Gaja'

signifies God from

whom the worlds have

come out and towards

whom they ate

progressing, to be

ultimately dissolved

in Him. The elephant

head is thus purely

symbolical and

points to this

truth.

Another factor we

observe in creation

is its two-fold

manifestation as the

microcosm (Suk~maI).qa)

and the Macrocosm (BrahmaI).qa).

Each is a replica of

the other. They are

one in two and two

in one. The elephant

head stands for the

macrocosm and the

human body for the

microcosm. The two

form one unit. Since

the macrocosm is the

goal of the

microcosm, the

elephant part has

been given greater

prominence by making

it the head.

Perhaps, the boldest

statement concerning

philosophi¬cal

truths ever made is

contained in that

pithy saying of the

Chandogya Upanisad:

'tat-tvam-asi,'

'That thou art.' It

simply means: 'You,

the apparently

limited individual,

are, in essence, the

Cosmic Truth, the

Absolute.' The

elephant¬human form

of GaI).apati is the

iconographical

representa¬tion of

this great Vedantic

dictum. The elephant

stands for the

cosmic whereas the

human stands for the

individual. The

single image

reflects their

identity.

Among the various

myths that deal with

GaI).apati' s

origin, the one that

attributes it to the

scurf or dirt taken

out of her body by

Parvati: seems to be

the most widely

known, and

considered as odd

and odious. It is

therefore

worth¬while to delve

a little deeper into

this mystery.

One of the epithets

by which GaI).apati

is well known and

worshipped is 'Vighnesvara'

or 'Vighnaraja'

('The Lord of

obstacles'). He is

the lord of all that

obstructs or

restricts, hinders

or prevents. With

the various grades

and shades of the

powers of

obstruction under

his control, he can

create a hell of

trouble for us if he

wantst In fact,

according to the

mythological

accounts, the very

purpose of his

creation was to

obstruct the

progress in the path

of perfection!

How does he do it?

If he is not

appeased by proper

worship, all

undertakings,

whether sacred or

secular, will meet

with so many

obstacles that they

will simply peter

out. This is to show

that nothing can

succeed without his

grace. If he is

pleased by worship

and service, he will

tempt his votaries

with success and

prosperity (Siddhi

and ~ddhi) the very

taste of which can

gradually lead them

away from the

spiritual path. Why

does he do it? To

test them thoroughly

before conferring

upon them the

greatest spiritual

boon of Mok~a. Being

the master of all

arts and

sciences, and the

repository of all

knowledge, he can

easily confer

success or

perfection in any of

these. However, he

is unwilling to give

spiritual knowledge

leading to the

highest spiritual

experience, lest it

should appear easy

of achieve¬ment in

the eyes of men.

Hence the severity

of the test. The

'- path of the good

is fraught with

innumerable

obstacles, 'sreyarhsi

bahuvighnani.' Only

the very best of

heroes, who can

brave the roughest

of weathers, deserve

to be blessed with

it. Human beings by

nature are inclined

towards the

enjoyments of the

flesh and

intoxications of

power and pelf. It

is only one in a

million that turns

towards God. Among

many such souls,

very few survive the

struggles and reach

the goal. (vide GUll

7.3)

When compared to the

highest spiritual

wisdom, which alone

is really worth

striving for, even ~ddhi

and Siddhi (success

and prosperity) are

like impurities,

Mala, as it were.

Since GaI:lapati' s

consorts are ~ddhi

and Siddhi

(personifications of

the powers of

success and

prosperity), he,

their spouse, has

been described as

created out of

Parvatt's bodily

scurf.

Again, the word 'Mala'

need not have any

odium about it. If

Siva represents

Paramapuru~a, the

Supreme Person,

Parvatt stands for

Parama Pralq1i,

Nature Supreme,

considered as His

power, inseparable

from Him. She is, in

the language of

philosophy,

Maya-pralq1i,

comprising the three

GUI:las~Sattva,

Rajas and Tamas.

Sattva is stated to

be pure and, as

compared to it,

Rajas and Tamas are

said to be 'impure'.

Since creation is

impossible out of

pure Sattva, even as

pure gold does not

lend itself to be

shaped into

ornaments unless

mixed with baser

metals, it has

got to be mixed with

Rajas and Tamas to

effect it. This

seems to be the

import of the story

of the 'impure'

sub-stances being

used by Mother

Parvatt to shape

GaI:lapatI.

Let us now try to

interpret the other

factors involved in

the symbology of

this god. His ears

are large, large

enough to listen to

the supplications of

everyone, but, like

the winnowing

basket, are capable

of sifting what is

good for the

supplicant from what

is not. Out of tbe

two tusks, the one

that is whole stands

for the Truth, the

One without a

second. The broken

tusk, which is

imperfect, stands

for the manifest

world, which appears

to be imperfect

because of the

inherent

incongruities.

However, the

manifest universe

and the unmanifest

unity are both

attributes of the

same Absolute. The

bent trunk is a

representation of

01'1kara or

PraI:lava which,

being the symbol of

Brahman, the

Absolute, is

declaring as it were

that GaI:lapati is

Brah¬man Itself. His

large belly

indicates that all

the created worlds

are contained in

him.

The Pasa (noose)

stands for Raga

(attachment), and

the Ailkusa (goad)

for Krodha (anger).

Like the noose,

attachment binds us.

Anger hurts us like

the goad. If God is

displeased with us,

our attachments and

anger will increase,

making us miserable.

The only way of

escaping from the

tyranny of these is

to take refuge in

God. Or it can mean

that it is far safer

for us to surrender

our attach¬ment and

anger to Him. When

they are in His

hands, we are safe!

How we wish that

Lord Ga1)apati had

chosen .a big

bandicoot as his

mount. The fact,

however, is

otherwise

. and that privilege

has been conferred

on a small mouse!

The word Mu~aka

(=mouse) is derived

from the root 'mu~'

which means 'to

steal'. A mouse

stealthily enters

into things and

destroys them from

within. Similarly

egoism enters

unnoticed, into our

minds and quietly

destroys all our

undertakings. Only

when it is

controlled by divine

wisdom, it can be

harnessed to useful

channels. Or, the

mouse that steals,

can represent love

that steals the

human hearts. As

long as human love

is kept at the low

level, it can create

havoc. Once it is

directed towards the

Divine, it elevates

us. The mouse that

is wont to see the

inside of all things

can stand for the

incisive intellect.

Since Gat:lapati is

the lord of the

intellect, it is but

meet that he has

chosen it as his

vehicle.

ICONS OF GAlfAPATI

There are several

varieties of

Ga1).apati icons

available in our

temples and

archaelogical

monuments. Whether

the number is

71,50,31, or 21, it

is certain that

there are several

aspects of this

deity. Only a few of

them can. be dealt

with here.

'Balaga1).apati' and

'Taru1).aga1).apati'

images depict him as

a child and a young

man, respectively. 'Vinayaka'

is shown with four

arms holding the

broken tusk, goad,

noose and rosary. He

holds the sweet

modaka in his trunk.

He may be standing

or. seated.

'Herambaga1).apati'

has five heads, ten

hands, three eyes in

each face and rides

on a lion. 'Vlravighnesa'

exhibits the martial

spirit with several

weapons held in his

ten hands.

'Saktiga1).apati,'

several varieties of

which are described

in the Tantras, is

shown with his Sakti,

called variously as

Lak~mI, Rddhi,

Siddhi,

Pu~!i and so on.

Worship of this

aspect is said to

confer special

powers or grant the

desired fruits

quickly.

One of the varieties

of this

'Saktiga1).apati' is

called

'Ucchi~!aga1).apati,'

the Ga1).apati

associated with

unclean things like

orts, whose worship

belongs to Vamacara

('the left-handed

path,' i.e., the

heterodox and

unclean path) and

said to give quick

results. There is

nothing to dread or

recoil in this

concept. Dirty

things are as much a

part of

nature as clean

things. But, do not

scavengers and

doctors handle them

in a hygienic way

and serve the

people? Are not all

people obliged to be

scavengers in

varying degrees? Why

not do it

religiously, as an

act of service and

worship? Nature

converts clean

things into unclean

things and vice

versa. Making

Ga1).apati preside

over it and handle

dirt scientifically

and religiously can

also be a spiritual

disci¬pline. This

seems to be the

philosophy behind

this concept.

'Nrttaga1).apati' is

a beautiful image

showing him as

dancing. It seems

once Brahma met

Gal).apati and bowed

down to him with

great devotion and

reverence. Being

pleased with this

Gal).apati started

dancing gracefully.

That

is why Gal).apati is

declared to be the

master of the arts

of music and

dancing.

'Varasiddhi Vinayaka'

is the aspect

worshipped dur-ing

the famous Gal).eSa

CaturthI festival.

He is said to be a

celibate.

Gal).apati is

sometimes depicted

as a Sakti (female

deity) under the

names of Gal).eSanI,

VinayakI,

Surpakafl).I,

Lambamekhala and so

on.

Gal).apati is

worshipped not only

in images but also

in LiIi.gas,

Salagramas, Yantras

(geometrica\

diagrams) and

Kalasas (pots of

water). Garyapati

Salagramas however,

are very rare. The

Svastika is also

accepted as a

graphic sym¬bol of

Garyapati.

Temples and shrines

dedicated to

Garyapati are very

numerous. They are

spread all over the

country. He appears

in the campuses of

temples of most

other deities also.

|

|