| |

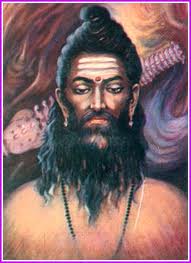

Agastyar, the patron

saint of southern

Indian's Tamil Nadu,

has become a figure

of mythology. He is

surrounded by

various legends of

several ages.

References to him

are found in the

literature of both

the Dravidian Tamil

land and also in the

Rig Vedic culture of

northern India. In

the Rig Veda, Agastyar is referred

to as one of the

seven great Rishis

of the Vedic period.

Several Vedic hymns

are ascribed to him. found in the

literature of both

the Dravidian Tamil

land and also in the

Rig Vedic culture of

northern India. In

the Rig Veda, Agastyar is referred

to as one of the

seven great Rishis

of the Vedic period.

Several Vedic hymns

are ascribed to him.

According to Vedic

legends, once upon a

time both Mitra, the

god of Love and

Harmony, and Varuna,

the god of the seas,

had a contest for

the love of a

heavenly damsel

Urvasi. They could

do no more than

deposit their

fertile seed: Mitra

in a pot and Varuna

in the sea. In time,

Agastyar was born

from the pot, and

Vasistha, one of the

reputed seven great

Rishis, started his

life from the sea.

Agastyar, being from

this divine

parentage, became

known also as "MaitraVaruni"

and "Ourvasiya". He

is known in Sanskrit

as Kalasaja,

Kalasisuta,

Kumbhayoni,

Kumbhasambhava,

Kumbamuni and

Ghatodbhava denoting

his origin from the

seed of Mitra. (Pillal,

1979, p. 254)

The correct

interpretation of

such legends is

still being awaited.

There are many

indications that

Agastyar existed as

a real historical

person. He had a

wife, Lopamudrai by

name, as well as a

sister and a son,

Sagaren. His wife

demonstrated

affection for him.

He is renowned for

combining

domesticity with a

life of austerity.

Agastyar ' s

ashrams

Tamil tradition

holds that at the

time of Shiva's

marriage to Parvati

on Mt. Kailas, the

assemblage of gods

and goddesses was so

great that the

equilibrium of the

planet was

disturbed. To

restore a balance,

Lord Shiva asked

Agastyar to travel

from Mt. Kailash to

southern India.

Geographically,

Agastyar's exodus to

southern India

divides itself into

three distinct

stages. The earliest

finds him lodged in

the Agastyasrama, a

few miles north of

Nasik, the ancient

Panchavati, on the

northern borders of

the Dandakaranya

Forest. His marriage

to Lopamudrai, the

daughter of the

Vidarbha King, and

Rama's first

interview with him

take place here. (Piuai,

1979, p. 254-57)

In the epic work

entitled Ramayana,

Rama tells his

brother Lakshaman,

as they are on their

way to Agastyar's

forest ashram, how

Agastyar saved the

world from a deadly

serpent. He also

narrated the story

of the death of

Vatapi in a manner

which differs from

that of the

Mahabharata, though

the deviations are

of no significance.

What is remarkable

is the idea that the

" Dandakaranya"

region was first

made fit for human

occupation by the

success of Agastyar

against the asuras

(demons). Agastyar's

conflict with the

asuras and rakshasas

(hostile powers of

the vital plane) is

also hinted at

elsewhere in the

Ramayana. For

instance, the sage

Visvamitra explains

to Rama the reason

for Tataka's attacks

on the Aryan

settlers. Agastyar

had destroyed

Tataka's husband

Sunda, and was

consequently

attacked by Tataka

and her son Maricha.

Agastyar cursed them

both, turning

Maricha into a

rakshasa and his

mother into an ugly

ogress. From that

time, to the moment

when Rama did away

with her, she kept

up a war of revenge.

(Pillai, 1979, p.

255)

Agastyar is now one

of the most famous

of holy men in

India. He is

considered to be a

great sage and

ascetic yogi and the

oldest teacher of

ancient times.

Though less than

five feet tall. he

was a fighter, a

famous hunter and an

archer, who

triumphed over

barbarous enemies,

and whom like

Hercules, of ancient

Greece, none could

approach in eating

and drinking.

The second stage of

Agastyar's

pilgrimage to the

South begins with

his residence at

Malakuta, three

miles east of Badami

(the ancient

vatapipura)

otherwise known as

Dakshinakasi, in the

Kaladgi District of

the Mumbai

Presidency. This now

residence is about

three hundred miles

south from his Nasik

ashram. During this

second stage he ate

Vatapi and destroyed

llvala (also known

as Vilvala) as

described above.

During the third

stage, there are

many stories about

him at Pothigai,

known also as the

Pothigai Hills, one

of the southern most

promontories of the

Western Ghats, in

the Pandya country.

During his residence

in the very center

of Tamil Nadu, he is

credited with having

founded the first

Tamil Academy or

Sangam, and having

presided over it,

besides writing an

extensive Tamil

Grammar and many

other works on

medicine, pharmacy,

alchemy, botany,

yoga, moral and

natural philosophy,

the education of

youth, religious

rites and

ceremonies,

exorcism, prayer,

mysticism and even

magic.

According to

tradition, in two

more stages of

migration, he

crosses the seas to

the Indonesian

Islands. Here he is

said to have visited

Barhinadvipa

(Borneo), Kusa Dvipa,

and Varaha Dvipa.

Here too he appears

to have taken up his

abode in the Maha

Malaya Hill in

Malaya Dvipa (now

known as Malaysia).

In the fifth stage

he crosses over to

the mainland and

enters Siam

(Thailand) and

Cambodia. It was

here, near the end

of his journey

eastwards, that he

was obliged to marry

a local beauty,

Yasomati by name,

and leave by her a

royal progeny among

whom King Yasovarma

was an outstanding

personage. (Pillai,

1979, p. 256-257,

262)

The most famous

ashram site, in the

Tinnevely district

near the Courtrallam

waterfalls in the

Pothigai mountains

of southern Tamil

Nadu, is where he is

reported to be

living to this day.

Babaji was initiated

into Kriya Kundalini

Pranayama here by

Agastyar.

In the epic

Mahabharata, the

story of Agastyar is

more fully

developed, and

Agastyar's

connection with

southern India comes

into prominence. His

marriage with

Lopamudrai, a

princess of Vidarbha,

is mentioned. The

princess had

demanded that to

claim the exercise

of marital rights,

Agastyar would have

to provide her with

the costly jewelry

and luxuries she was

used to in her

father's house,

without in any

manner jeopardizing

his ascetism.

Agastyar could only

meet his wife's wish

by seeking a large

gift of wealth. lie

approached three

Aryan kings one

after another, but

in vain. They all

went to Ilvala, the

"daitya" (demon)

king of Manimati.

Ilvala was no friend

of the Brahmins

because one of them

had refused to grant

him a son equal to

Indra. His vengeance

took a bizarre form.

He would transform

his younger brother

Vatapi into a male

goat and offer his

brothers flesh to

the Brahmins as

food. After doing so

he would suddenly

recall Vatapi back

to life, who would

rip open the flanks

of the Brahmins as

he emerged laughing.

In this manner the

two brothers killed

many Brahmins and,

on the occasion of

the visit of

Agastyar and the

three kings, Ilvala

tried to play the

same game. He

prepared the flesh

of Vatapi to

entertain them. The

kings became

unhappy. Agastyar

ate it all, and when

Ilvala called for

Vatapi to come back,

only air came out of

Agastyar's stomach,

because Vatapi had

been digested. Then

Ilvala, becoming

unhappy, promised to

give wealth to

Agastyar if the

latter could tell

him what he intended

to give. Agastyar

was able to predict

Ilvala's intention.

The kings and

Agastyar returned

with the wealth they

needed. Vatapi is

the name of the well

known fortified city

in the western

Deccan which was the

capital of the early

Chalukyas. This city

is now called Badami.

This story may be

understood to mark

the beginning of

Agastyar's

connection with

southern India. (Pillai,

1979, pg. 255)

The Mahabharata also

records the story of

Agastyar drinking up

the waters of the

ocean to enable the

gods (devas) to

dispose of their

enemies who were

hiding under the

sea; and of his

journey to southern

India on some

unspecified business

when he prevailed

upon the Vindhya

mountains to stop

growing until he

returned, which

however, he never

did. The pact with

the Vindya mountains

and the drinking of

the waters of the

ocean have been

generally accepted

as allegorical

representations of

the spread of Aryan

culture first to

India south of the

Vindhyas, and then

across the seas to

the islands of the

archipelago and to

Indo-China. It is

supported by other

accounts of the life

of Agastyar.

Agastyar and the

Tamil language and

grammar

Traditionally

Agastyar is

considered as the

father of the Tamil

language and

grammar, and the

royal chaplain (kulaguru)

of the divine line

of Pandiyan rulers.

These rulers were

the descendants of

Shiva and Parvati

who condescended to

become the first

king and queen of

this celebrated

line. Kulasekhara

Pandiyan founded the

Pandiyan dynasty at

South Madurai, the

capital of the

ancient Tamilagam,

lying far south of

the present

southernmost point

of India.

His treatise on

Tamil grammar is

said to have

contained no less

than 12,000 sutras

or aphorisms. Except

for some fragments

which have been

preserved in

quotations by

Tolkappiyanar in his

work on the same

subject, Tolkappiyam,

it has not survived.

(Pillai, 1979, p.

264)

At what period

Agastyar established

himself in southern

India is not known.

It will remain so

until the real date

of the existence of

the king Kulasekhara

Pandiyan, who

patronized Agastyar,

is ascertained. All

accounts concur in

assigning the

foundation of the

Pandiyan kingdom at

Madurai to

Kulasekhara Pandiyan;

but they are at

considerable

variance with regard

to the time when

that event happened.

When Agastyar left

the court of

Kulasekhara Pandiyan,

he is stated to have

assumed the ascetic

life, and to have

retired to the

Pothigai Hills,

where he is commonly

believed to be still

living in anonymity.

There is no clear

and specific

reference to

Agastyar and or his

exploits, in any of

the early Tamil

works now known.

Only some indirect

ones are made in the

anthologies of the

Sangam Age. The

phrase "sage of

Pothigai" (Pothigal

being the

southernmost section

of the western Ghats)

is an indication

that the legends

relating to Agastyar

were not unknown in

the land at the

time. Vasishtha, the

author of the poem

Manimckalai, a

Buddhist epic, know

of his miraculous

birth. The same

author also says

that Agastyar was a

friend of the Chola

king, Kanta. At the

request of Kanta he

released the Cauvery

river from his water

pot.

Agastyar's abode was

in the Pothigai

mountains.

Naccinarkkiniyar

(1400 A.D.) a

commentator of the

Middle Ages,

narrates (on the

authority of a more

ancient writer) that

when Havana, the

king of the asuras

in the Ramayana,

came to the Pothigai

Hills, and was

tyrannizing the

inhabitants of the

extreme southern, he

was persuaded by

Agastyar to leave

that land alone and

go to the island of

Sri Lanka. (Pillai,

1979, p. 258;

Zvolebil, 1973, p.

136) References to

Agastyar's work on

Tamil grammar appear

rather late. The

first occurs in the

legend of the three

Sangams, the ancient

Tamil literary

academies, narrated

in the

Iraiyanar-Agapporul

Urai, a work of the

ninth century A.D.

Here Agastyar is

mentioned as a

leader of the first

and second Sangams,

which lasted for

4,400 years and

3,700 year

respectively. His

work Agastyam miss

aid to have been the

grammar of the first

Sangam, while that

work, together with

the Tolkappiyam and

three other works,

formed the basis for

the second Sangam.

According to

fraiyanar-Agapporul

Urai, the third

Sangam lasted for

1,850 Years. (Pillai,

1979, p. 258-259)

Whether Agastyar

wrote a treatise on

Tamil grammar, and

if so in what

relation that work

stood to the

Tolkappiyam, the

oldest extant work

on the subject, has

been discussed by

all the great

historians and

commentators of the

Tamil country.

Perasiriyar

(1250-1300 A.D.)

says that in his day

some scholars

contended that

Tolkappiyanar, the

author of the

grammar named after

him, composed his

work on principles

other than those of

the the Agastyam,

following in this

other grammars which

have not survived.

He refutes this

theory by an appeal

to tradition and

authority,

particularly that of

lraiyanar Agapporid

Urai. He maintains,

with support from

more ancient

writings, that

Agastyar was the

founder of the Tamil

language and

grammar, that

Tolkappiyam was the

most celebrated of

the twelve pupils of

the great sage, that

the Agastyam was the

original grammar,

that Tolkappiyanar

must be hold to have

followed its

teachings in his new

work, and that

Agastyar's work must

have been composed

before the Tamil

country was

confined, by an

inundation of the

sea, to the limits

indicated by

Panambaranar in his

preface to the

Tolkappiyam, i.e.,

from Vengadam hill,

to Cape Cormorin. (Pillai,

1979, p. 259).

The opposite party

that denied

Tolkappiyanar's

indebtedness to

Agastyar did not

give up its

position. The

general belief that

Tolkappiyanar was a

disciple of Agastyar

was too strong for

them to deny, so

they "postulated

hostility between

teacher and pupil

arising out of

Agastyar's jealousy

and hot temper". (Sastri,

1966, p. 365393).

Naccinarkkiniyar

records the story

that after his

migration to the

south, Agastyar sent

his pupil

Trinadhumagni (Tolkappiyanar)

to bring his wife

Lopamudrai from the

North. Agastyar

proscribed that a

certain distance

should be maintained

between the pupil

and his wife during

their journey, but

when the rising of

the Vaigai

threatened to drown

Lopamudrai,

Tolkappiyanar

approached too close

in holding out to

her a bamboo pole

with the aid of

which she reached

the shore in safety.

Agastyar cursed them

for violating his

instructions saying

that they would

never enter heaven.

Tolkappiyanar

replied with a

similar curse on his

master. (Pillai,

1979, p. 259;

Zvolebil, 1973, p.

137)

As K.A. Sastri says,

this legend

"represents the last

phase of a

controversy,

longstanding,

significant and by

no means near its

end even in our

time" (Sastri, 1966,

p. 77). Much more

research must be

done among the

thousands of palm

leaf manuscripts and

other documents

which have been

collected in such

places as the

Oriental Manuscripts

Library in Madras,

the Saraswati Mahal

library in Tanjore,

the libraries of the

Palani Temple, the

Palayamkottai Siddha

Medical College, and

those in the hands

of private

collectors and

siddha medical

practitioners.

The affirmation and

denial of Agastyar's

father ship of Tamil

and of his work

being the source of

the Tolkappiyam are

both symbolic of

divergent attitudes

towards the incoming

northern Sanskritic

influences. As a

matter of fact,

there is no mention

of Agastyar either

in the Tolkappiyam

nor in the

Panambaranar's

preface to it. The

earliest reference

to the Agastyam

occurs only in the

eighth century A.D.,

as we have seen, and

that is also the

time when Pandiyan

chroniclers begin to

proclaim the

preceptor ship of

Agastyar to the

Pandiyas, the

patrons of Tamil

literature and the

Sangam, and the

first genuine Tamil

power to achieve

political expansion

and to establish an

empire. Many of the

stories meant to

support Agastyar's

connection with

Tamil and

Tolkappiyanar may

have been elaborated

in subsequent ages.

The attempt to give

Agastyar the

dominant position in

the evolution of

Tamil culture evoked

a challenge. Things

went on smoothly so

long as Aryan

influence, the

influence of the

"Northern" speech

and culture, was

content to penetrate

the Tamil land

quietly and by

imperceptible

stages, and silently

transform the native

elements. This

process began very

early and was

accepted by the

Tamils to an extent

that has rendered it

all but impossible

to distinguish the

elements that have

gone to make up the

composite culture.

But when a theory

was put forward,

that is when a

legend may have been

invented: to show

that Tamil as a

spoken language and

with it the entire

culture of the Tamil

country was derived

from a Vedic seer.

This was met,

naturally, by a

counter-assertion

and the elaboration

of legends in the

opposite sense.

The main legends

gathered around

Agastyar in the

north and in the

south are on

parallel lines and

are filled with

miraculous deeds.

There are several

local and temporal

variations. The

Himalayan mountain

of the northern

legend is replaced

by the Pothigai of

the South.

Agastyar's

composition of many

Rig Vedic hymns and

medical works in

Sanskrit is answered

by his numerous

mystic and medical

treatises in Tamil;

his efforts to bring

down the Ganges with

the consent of Shiva

finds an echo in his

getting Tamraparni

from Shiva and his

bargaining with God

Ganesha for Cauvery;

his seat in Kasi (Bonares)

seems to be replaced

by his abode in

Badami, known as

Daksina Kasi; his

marriage with

Lopamudrai, the

daughter of a

Vidarbha King, has a

parallel in his

wedding of Cauvery,

the daughter of King

Cauvery; and taking

into consideration

the curses, which

had issued from his

spiritual armory in

the north, his curse

of Tolkappiyanar,

his own student,

shows unmistakably

how the dwarf sage

kept true to his

reputation and

habits, in the

far-away south (Pillai,

1979, p. 258-261).

Agastyar ' s

contributions to

science

There are hundreds

of ancient treatises

from various areas

of science ascribed

to Agastyar. These

include medicine,

chemistry, pharmacy,

astronomy and

surgery. As a

physician, Agastyar

occupies the same

eminence amongst the

Tamils as

Hippocrates does

amongst the Greeks,

and it is remarkable

that there are some

very curious

coincidences between

the doctrines of the

former and those of

the latter,

especially as

regards the

prognosis and

diagnosis of

diseases, the

critical days, and

premonitory symptoms

of death. The

existence of seminal

animalcules, which

was discovered by

Ludwig Hamm in

Europe only in 1677

A.D., is mentioned

by Agastyar in one

of his medical

works, entitled

Kurunadichutram (PiUai,

1979, p. 265).

Below is a list

of manuscripts

attributed to

Agastyar, as

mentioned in a 160

year old

bibliography of

Siddha medical

literature:

1. Vytia Vaghadum

Ayrit Anyouroo (Vaidya

Vahadam 1500)

A medical work by

Reeshe Aghastier: it

is written in Tamil

poetry, and consists

of 1,500 verses.

2. Tunmundrie

Vaghadum (Dhanvanthari

Vahadam)

A medical work,

originally written

by Tunmundric in

Sanskrit, and

translated into

Tamool verse by

Aghastier. It

consists of 2,000

verses. The Hindu

practitioners hold

it in high

veneration, for the

particular account

it gives of many

diseases, and the

valuable receipts it

contains.

(Manuscripts

available at

Palayamkottai)

3. Canda Pooranwn:

A work on ancient

history, originally

written in Sanskrit

verse, by Resshe

Aghastior and

afterwards

translated into

Tamool by Cushiapa

Braminy. It consists

of 1,000 stanzas.

4. Poosavedy:

This book treats of

the religious rites

and ceremonies of

Hindus. It was

written by Aghastier,

and consists of 200

verses. (Ms.

available at Tanjore

and Madras)

5. Deekshavedy (Deeksha

Vithi):

A work which treats

of magic and

enchantment, on the

use and virtues of

the rosary, and on

the education of

youth: it consists

of 200 verses, and

was written by

Agastyar (Ms.

available in Tanjore

and Madras)

6. Pemool (Peru Nul)

A medical work,

written by Agastyar,

in high Tamool. It

consists of 10,000

verses, and treats

fully of all

diseases, regimen

(Ms. available at

Palayamkottai)

7. Poorna Nool:

This book consists

of 200 verses. It

was written by

Aghastier, and

treats chiefly of

exorcism: it also

contains many forms

of prayer.

8. Poorna Soostru: A

work on the

intuition of

religious disciples,

and on their forms

of devotion, and

which

also treats of the

materia medica and

regimen. It was

written by Agastyar

and consists of 216

verses. (Ms.

available at Madras

and Palani and also

printed)

9. Curma Candum

(Karma Kandam)

A medical shaster of

Agastyar, written in

Tamool verse, and

consists of 300

stanzas: supposed to

be translated from

the Sanskrit of

Durmuntrie. It

treats of those

diseases which are

inflicted on mankind

for their folhes and

vices. (Manuscripts

available at Tanjore

and Madras and also

printed)

10. Agastyar Vytia

Ernoot Unjie (Aghastior

Vaidyam 205)

A work on medicine

and chemistry,

written by Agastyar

in Tamool verse, and

consisting of 205

verses. (Ms.

available at Palani)

11. Agastyar Vytia

Nootieumbid (Agastyar

Vaidyam 150)

A work in Tamool

verse, written by

Agastyar. It

consists of 150

stanzas, and treats

of the purification

or rendering

innocent, of

sixty-four different

kinds of poison

(animal, metallic,

and vegetable), so

as to make them

safe, and fit to be

administered as

medicine (Ms.

available at Palani

and printed)

12. Agastyar Vytia

Vaghadum Napotetoo (Agastyar

Vaidya Vahadum 48):

A medical shaster,

written by Agastyar,

in Tamool verse;, on

the cure of

gonorrhea; and

consisting of 48

stanzas.

13. Agastyar Vytia

Padinarroo (Agasthiyar

Naidyam 16):

A medical shaster,

written by Agastyar,

in Tamool, and

consisting of 16

verses. It treats of

the diseases of the

head, and their

remedies.

14. Agastyar Vytia

Eranoor (Agastyar

Vaidyam 200):

A medical shaster,

written by Aghastier

in 200 Tamool

verses. It treats of

chemistry and

alchemy (Ms.

available at

Palayamkottai and

printed).

15. Calikianum (Kalai

Gnanam):

A work on theology,

written in Tamool

verse, by Agastyar,

and consisting of

200 stanzas (Ms.

available at Tanjore)

16. Mooppoo (Muppu):

A medical shaster

written by Agastyar,

in Tamool verse, and

consisting of 50

stanzas. It treats

of the eighteen

different kinds of

leprosy and their

cure. (Ms. available

at Thirupathi)

17. Agastyar Vytia

Ayrit Eranoor (Agastyar

Vaidyam 1200): A

Medical shaster,

written by Agastyar,

in

Tamool verse and

consisting of 1200

stanzas. It treats

of botany and of

Materia Medica. (Ms.

printed).

18. Agastyar's Vytia

Ayrnouroo (Agastyar

Vaidyam 500):

A valuable work on

medicine, written by

Agastyar, in Tamool

verse and consisting

of 500 stanzas. It

treats very fully of

many diseases, and

contains a great

variety of useful

formulae.

19. Agastyar Vytia

Moon-noor (Agastyar

Vaidyam 300):

A work on pharmacy,

written by Agastyar,

in Tamool verse, and

consisting of 300

stanzas. (Ms.

available at

Palayamkottai and

printed)

20. Agastyar

Vydeyakh Moonooro

(300 verses): This

chiefly instructs us

in the art of making

various

powders.

21. Agastyar

Auyerutty Annooroo

(1500 verses):

A general work on

Materia Medica. (Ms.

available at Tanjore,

Madras and Palani)

22. Agastyar

Aranooroo (600

verses): (Ms.

available at Tanjore

and Palani)

23. Agastyar Moopoo

Anbadoo (50 verses)

(Agastyar Muppu 50)

24. Agastyar

Goonnoovagadam

Moonoor (300 verses)

(Agastyar Guna

Vahadam 300): Ms.

available at Tanjore,

Thirupathi, Palani

and Palayamkottai

also printed.

25. Agastyar

Dundakum Nooroo (100

verses). (Agastyar

Thandaham 100):

These are various

Works of Agastyar on

chemistry and

physic. They also

treat of theology,

and of the best

means of

strengthening the

human frame. (Ms.

available at Tanjore

and Madras.)

(Pillai, p. 268-70).

Agastyar is said to

have had twelve

disciples to whom he

taught the different

arts and sciences,

and who were

afterwards employed

by him in

instructing the

people.

The names of

these disciples are

1.

Tolkappiyanar

2. Adankotasiriyanar

3. Turalinganar

4. Semputcheyanar

5. Vaiyabiganar

6. Vippiyanar

7. Panambaranar

8. Kazharambanar

9. Avinayanar

10. Kakkypadiniyar

11. Nattattanar

12. Vamanar

but few

particulars are

known about them.

Other prominent

disciples included Thiruvalluvar, the

author of the

perennial classic of

Tamil literature,

Thirukural, and

Babaji Nagaraj, the

fountainhead of

Kriya Yoga

Siddhantham in the

modern age. Their

influence on the

world today is

immeasurable, and

will be discussed in

subsequent chapters.

Agastyar is a sage

of cultural

integration, leading

a fusion of the

culture of the

northern Aryans with

that of the southern

Dravidians. His

ashram was the

practical approach

to harmony and

integration,

enabling every

visitor to worship

the Absolute in his

or her own way.

There were separate

shrines to different

deities and an

illuminating shrine

to Righteousness.

Kamban says Agastyar

welcomed Rama in the

sweet, pleasant

tamil language,

while his disciples

chanted Vedic hymns.

This may be seen in

the story that

Agastyar was

specially sent down

to the south by Lord

Shiva himself, at

the time of His

wedding with Parvati

on the Himalyas. The

north sank low under

the weight of the

crowding celestials

while the south rose

up, free of such

burden, and the

diminutive sage was

sent south to right

the tilt. Was it

because at that time

the south had

forgotten its gods

or that the north

had become too full

of gods, masking the

image of the single

Absolute? Anyway it

was Agastyar who

propagated an

integral, harmonious

culture. The

immortal message and

spiritual technology

of Kriya yoga, which

he taught to Babaji,

may be the master

key to the cultural

integration which is

now needed in the

modern world, where

telecommunications

and computer

technology have

created an

interdependent

"global village".

May the name of this

great sage inspire

us to righteous and

harmonious action in

these troubled

times! May integral

institutions

flourish!

|

|